* From Pew Charitable Trusts…

With mental illness and drug addiction surging across the United States, it’s more likely than ever that emergency calls could involve a person experiencing a mental health or substance use crisis. Those calls are often received by 911 call centers, which recent Pew research suggests lack the resources and training needed to dispatch tailored responses. Instead, law enforcement officers typically are sent to manage situations that often require specialized services related to health, mental health, and housing.

New research from the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute, in partnership with The Pew Charitable Trusts, suggests that a program developed in Dallas might serve as a blueprint for policymakers who want to move their crisis response systems toward a health-centered approach instead of relying solely on police.

Since 2018, the city has employed a multidisciplinary model known locally as Rapid Integrated Group Healthcare Team (RIGHT) Care, which brings together teams of mental health professionals, paramedics, and specialized law enforcement officers who can better direct people in distress to community-based care and services. According to the Meadows Institute report, these teams responded to 6,679 calls from Jan. 29, 2018, to June 7, 2020. The analysis found that:

• 62% resulted in a connection to care (community service, or voluntary or involuntary hospitalization).

• 40% resulted in a connection to some sort of community service, such as a referral to health or housing services.

• 29% were resolved on scene with no further services needed.

• Only 14% resulted in emergency detention.

• 8% resulted in a person being taken to a hospital or psychiatric facility.

• Only 2% resulted in arrests for new offenses.

• While mental health visits to the emergency department at Dallas’ Parkland Hospital increased by 30% from 2017 to 2019, areas served by RIGHT Care saw a 20% decrease in mental health-related admissions.

Emphasis added.

* More…

In addition to the on-patrol three-member units, Parkland provides the RIGHT Care team with licensed mental health professionals to assist with navigating 911 calls involving behavioral health crises. That’s important, because recent research by Pew suggests that few 911 call centers have staff with the training or resources needed to manage these calls and dispatch appropriate responses. Dallas’ initial success shows how a properly resourced call center can improve outcomes.

Based on the positive data from Meadows—a Dallas-based, data-driven nonprofit focused on providing efficient behavioral health care to Texans when and where they need it—city officials earlier this year expanded RIGHT Care throughout the city. They added two new teams, increasing active units from nine three-person units to 15, and moving closer to the goal of RIGHT Care responding to 40% of mental health calls in the city.

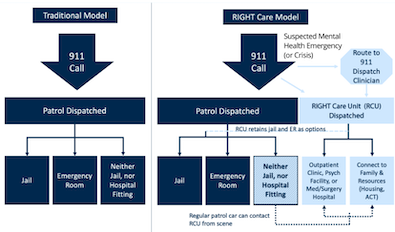

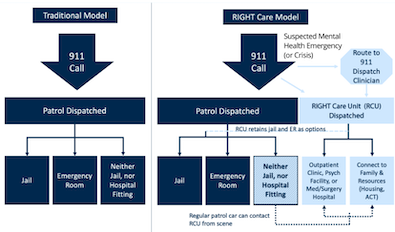

* Flow chart from the study…

The added benefit here is the amount of stress this approach can take off of responding police officers, who already have high-stress jobs.

- Keyrock - Tuesday, Dec 14, 21 @ 1:04 pm:

Excellent information. Thanks, Rich.

- charles in charge - Tuesday, Dec 14, 21 @ 1:36 pm:

Seems like something Chicago should be seriously investigating, in light of the Sun-Times’ recent reporting about decades of “dead-end arrests” for low-level drug possession.

https://chicago.suntimes.com/2021/11/26/22639255/dead-end-drug-arrests-drugs-possession-chicago

- Almost Retired - Tuesday, Dec 14, 21 @ 2:48 pm:

In the mid 1970’s in Peoria, the mental health center responded with police to mental health, substance use and sometimes domestic violence. They were 24/7 and even had bibles in their cars. That program had federal funds. In early 80s the Decatur Mental Health Centers crisis team went out with the Decatur and it County officers on mental health calls and substance abuse. This was State funded. The Feds stopped funding it in the 70s and The State stopped funding in late 80s. In both situations it facilitated positive productive relationships between law enforcement and the mental health and substance abuse professionals. With Medicaid being principle funder of mental health services there is for most part no funds that support this type of service. Twice in my career where I worked it was standard operating procedure. It obviously disappeared because no one wanted to fund it. This isn’t new and should have been SOP by now.

- Almost retired - Tuesday, Dec 14, 21 @ 2:49 pm:

bibles shoul have been bubbles-sorry

- Kyle Hillman - Tuesday, Dec 14, 21 @ 2:49 pm:

As we have said for years, a mental health crisis is a medical crisis not a crime. It should be treated as such. While the study continues to prove that mental health teams are effective, we still support a model that doesn’t include a law enforcement officer as a member of that team. We don’t send officers along on calls with EMTs why must we with LCSWs?

There are plenty of models (like what is happening in Oregon) that shows policy makers that you do not need an armed officer on these calls.

- Leslie K - Tuesday, Dec 14, 21 @ 3:00 pm:

charles @1:36pm–Chicago has rolled out a very small pilot program of a co-responder model, with plans to expand:

https://www.ems1.com/mental-health/articles/chicago-pilot-program-partners-mental-health-clinicians-medics-police-boNLeyOnUjaZxrnp/

- Dotnonymous - Tuesday, Dec 14, 21 @ 3:38 pm:

A conversation overheard between a person in need of medication and a prison guard while being transferred (cuffed & shackled) on a prison bus.

Prisoner: ” Please, I really need my meds.”

Guard: (thumping nightstick into palm) ” If you don’t shut up…I’ve got something for you, better than your pills”.

- Dotnonymous - Tuesday, Dec 14, 21 @ 3:49 pm:

One can not penalize one’s way to mental health…or can society by imprisoning Citizens who suffer from the disease of Addiction.

End the War on Drugs…which was all ways a war on people.