* Background is here if you need it. Quick summary of Snyder v. United States from the SCOTUS Blog…

Whether section 18 U.S.C. § 666(a)(1)(B) criminalizes gratuities, i.e., payments in recognition of actions a state or local official has already taken or committed to take, without any quid pro quo agreement to take those actions.

The ComEd Four defendants believe the outcome of this case could overturn at least some of their convictions. And former House Speaker Michael Madigan was able to get his trial delayed until after this decision comes down.

* New development yesterday…

* As noted above, the heart of this is the definition of gratuities. The US Attorney’s office believes gratuities are covered under the criminal statute in question. “I wish somebody would just read the language of the statute,” Assistant US Attorney Amarjeet Bhachu said last month.

The defense, however, read the statute and, unsurprisingly, sees things in a different light. Here’s one of the statutes with highlights…

corruptly solicits or demands for the benefit of any person, or accepts or agrees to accept, anything of value from any person, intending to be influenced or rewarded in connection with any business, transaction, or series of transactions of such organization, government, or agency involving any thing of value of $5,000 or more

Two of the key words there are “rewarded” and “corruptly.” The feds say Congress clearly meant gratuities when it used the word “rewarded.” The defense begs to differ…

The government obtained a conviction below on the theory that merely knowing that a gift was meant as a reward for official conduct qualifies as acting “corruptly.” Under that theory, it is irrelevant whether the gift is worth $1, $100, or $100,000; all that matters is awareness that the gift is thanks for official conduct.

The government now argues that “corruptly” refers to unspecified wrongfulness. But the government cannot defend a conviction on a new theory on which the jury was not instructed. And the government never says what separates innocuous from wrongful gratuities, let alone how ordinary citizens would have notice of that dividing line.

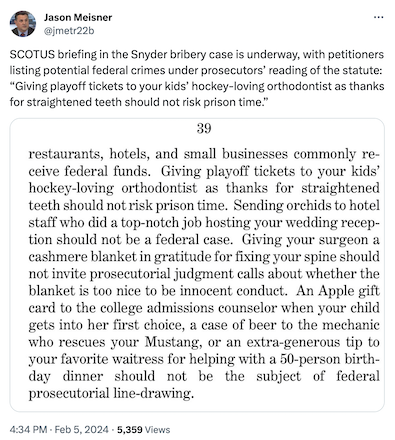

Keep in mind the federal law also applies to “private companies and nonprofits that accept at least $10,000 in federal funds”…

This Court has repeatedly rejected similarly sweeping and amorphous interpretations that would extend federal criminal law to commonplace conduct that States and localities ordinarily regulate. Congress did not plausibly upend the federal-state balance and impose potential ten-year prison terms on 19.2 million state and local officials, thousands of tribal officials, and millions of private employees for accepting gifts as thanks for on-the-job acts. It is even less conceivable that Congress subjected state, local, and tribal officials to such lengthy prison terms when the federal gratuities statute imposes a maximum two-year sentence on federal officials, whose ethics are extensively regulated by the federal Office of Government Ethics. Congress surely did not contemplate that federal prosecutors might treat every political contribution—a form of core First Amendment activity—as a potentially unlawful gratuity.

The far more natural reading of section 666 is simple: the provision criminalizes all forms of bribery. By prohibiting “corruptly … accept[ing] … anything of value …, intending to be influenced or rewarded” in official business, Congress employed all the hallmarks of a bribery statute. Bribery involves wrongfully and deliberately trading official conduct for money. Congress used “intending to be influenced or rewarded” to cover the waterfront of inducements. Using “rewarded” makes clear that officials still engage in bribery if they take money in exchange for official conduct and claim they would have acted the same way regardless, or take money after the fact. Those officials “intend[] to be … rewarded” with money in exchange for taking some promised action.

Congress routinely uses similar language in other bribery statutes, and routinely uses dramatically different language when criminalizing gratuities. Congress famously does not hide elephants in mouseholes, and Congress did not camouflage a gratuities crime deep within a provision targeting bribery.

There’s more.

Thoughts?

- ElTacoBandito - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 12:55 pm:

So basically all you have to do is get a reputation for rewarding politicians who do your bidding and then you’re home free. Don’t even have to meet with elected officials, just give a nice campaign donation or vacation after the work and they can never prove a quid pro quo.

- Chicagonk - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:01 pm:

My bet would be a narrow decision upholding the conviction. Common sense should hopefully prevail here - Businesses don’t just hand out $13,000 as a thank you.

- Da big bad wolf - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:07 pm:

=== Businesses don’t just hand out $13,000 as a thank you.===

Except some members of the Supreme Court themselves have gotten lavish gifts as thank yous. Why would they say others can’t do the same thing?

- Dotnonymous x - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:11 pm:

- And the government never says what separates innocuous from wrongful gratuities,… -

A fatal mistake…in my (G.E.D. backed) legal opinion.

- vern - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:12 pm:

Seems pretty simple to distinguish politicians from the other professions in the examples - politicians don’t work for specific clients. Their duty is to their constituents generally. If orthodontists had to choose which teeth to fix based on the general good, paying them for working on your kid would be a lot more corrupt.

“It’s not a bribe, it’s a gratuity” is pretty risible. They’re telling me it’s raining, and my leg is wet, but I suspect it’s not actually raining.

- Anyone Remember - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:13 pm:

“So basically all you have to do … .”

Sadly, that is SCOTUS’ track since they overturned most of Otto Kerner’s convictions 50 years ago.

- Rich Miller - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:22 pm:

===Seems pretty simple to distinguish politicians from the other professions in the examples===

Except if they received at least $10K from the feds.

- Three Dimensional Checkers - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:27 pm:

Corruptly is a specific intent crime. The defense seems to construe the statute to have no mens rea. It is arguing against a straw man. Flowers for your bell boy is not a crime because it is not an act done corruptly.

The USA has been clear that they have enough evidence to prosecute Madigan either way too.

- Da big bad wolf - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:33 pm:

=== The defense seems to construe the statute to have no mens rea. It is arguing against a straw man. Flowers for your bell boy is not a crime because it is not an act done corruptly.===

I think their argument is there is no way to know if the defendant has mens rea since people can’t read minds.

- Dotnonymous x - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:36 pm:

Criminal mind must be demonstrated by a show of proof…beyond a reasonable doubt…no more, and no less.

- Sue - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:45 pm:

Problem for the govt with this statute is that every defendant is entitled to a clear unambiguous understanding of when conduct is criminal

- Rich Miller - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:47 pm:

Gonna agree with Sue on this.

- Dotnonymous x - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:51 pm:

- The USA has been clear that they have enough evidence to prosecute Madigan either way too. -

I can’t tell…so far.

- Anon324 - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 1:53 pm:

==The defense seems to construe the statute to have no mens rea. It is arguing against a straw man. Flowers for your bell boy is not a crime because it is not an act done corruptly.==

The brief from the defense says the opposite. The argument is that the prosecution removed the specific intent required of a corrupt act in order to criminalize the activity. That flowers for the bell boy is not corrupt is exactly their point: the flowers were provided in return for taking official action, and under the prosecution’s theory used to obtain the conviction, the bell boy knowing that it was for the official action inherently makes his receipt of the gratuity corrupt.

From the brief:

“Section 666’s “corruptly” mens rea element further

undercuts the notion that Congress criminalized gratuities. Bribery statutes routinely use “corruptly” to

describe deliberately and wrongfully agreeing to a quid

pro quo. Yet the jury instructions treated “corruptly” as

a mere knowledge requirement, asking whether Ma

yor Snyder “underst[ood]” that the payment was a gratuity.

J.A.28. That instruction drains “corruptly” of meaning, since “intending to be influenced or rewarded” already requires knowledge. By contrast, the government’s brief in

opposition defines “corruptly” as “wrongful, immoral, depraved, or evil.” BIO 14 (citation omitted). That dramatic

shift in defining the mens rea of a criminal statute alone

requires reversal.”

- Annon'in - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 2:49 pm:

Isn’t true that district courts in 2 circuits have ruled similar acts are not crimes?

- Section 666 - Tuesday, Feb 6, 24 @ 2:49 pm:

The feds got it wrong. Congress also did not intend for me to be used to burnish résumés.